Sunday in the Park with George

National Theatre London

Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by James Lapine

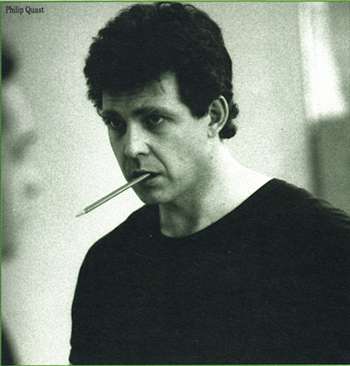

Lawrence Olivier Awards for Best New Musical & Best Actor in a Musical for Philip Quast

- Directed by Scott Pimlott

- Designed by Tom Cairns

- Lighting by Wolfgang Gobbel

- Orchestrations by Michael Starobin

- Musical Direction by Jeremy Sams

- Choreography: Aletta Collins

- Chromolume #7: Martin Duncan

- Sound: Mike Clayton, Paul Groothius

- Conductor: John Jansson

Cast:

- Philip Quast - George Seutrat/George his Grandson

- Maria Friedman - Dot/Marie

- Michael O'Connor - Franz/Dennis

- Nyree Dawn Porter - Yvonne/Naomi Eisen

- Gary Raymond - Jules/Bob Greenberg

- Megan Kelly - Celeste #1 -

- Clare Burt - Celeste #2/Betty

- Matt Zimmerman - Mr./ Charles Redmond

- Vivienne Martin - Mrs./ Billie Webster

- Sheila Ballantine An Old Lady/ Blair Daniels

Synopsis

Inspired by the art of Georges Seurat, the nineteenth-century pointilliste painter, specifically a painting entitled "A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte,"

Act1 A Sunday in Paris in 1884. Georges, an artist who is experimenting with innovative painting techniques, is seated in front of a bare white stage, blank drawing-pad in hand. He is trying to paint a study of his mistress, Dot, on an island somewhere in the Seine. Dot is not turning out to be the most cooperative subject, fidgeting and complaining. For Dot, it's just another SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE.

In the painter's studio, Dot sits at a vanity mirror powdering her face, while, in an identical rhythm, Georges dabs spots of red and purple and white on his new painting: it's only COLOUR AND LIGHT. She is preparing to go to the Follies with him, but his painting proves more important -he has to stay to finish a hat. Dot leaves in a rage, realising that for Georges, his art will always come first.

Returning to the park on another Sunday sometime later, Georges paints two women. George has created a work of art incorporating order, design, symmetry, balance and harmony. Unfortunately, burying oneself in one's work can often cause certain unforeseen repercussions. Dot, pregnant, has a new lover, a baker called Louis. She has left Georges. Georges is sorry Dot has left, but that is his life: he watches the world go by, while he sits at his easel, lost in some tiny detail. What George doesn't know is that Dot is carrying his child.

Back in the park, with characters, squabbling and fighting until Georges calls for "order" and "balance". He commences to re-arrange the people and the trees and, from the chaos, assembles a peaceful promenade on La Grande Jatte. Harmony at last. As the fractious ensemble comes together to form his painting, Georges freezes his models in their final poses: an ordinary, perfect SUNDAY.

In Act Two, we jump to 1984 where another George, the grandson of the daughter Dot bore to George in Act One, has been commissioned to create a piece of mechanical performance art to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his great-grandfather's painting.

It is still a Sunday afternoon on the island of La Grande Jatte. But the serenity of the final tableau has degenerated into petty bickering among the figures in the painting. These people have been stuck in the same poses for almost a century and they're sick of it.

After some technical hitches, the machine finally functions and George and Marie narrate the history of Georges Seurat. George is making the deal so that he can finish the art: connections lead to commissions lead to exhibitions. As the glittering guests drift off to dinner, Marie looks at her mother in the painting, remembering what she said about children and art and trying to relate her to her young grandson.

George, however, is at a creative impasse he has begun to question whether he is finished as an artist. He visits Paris and the island of La Grande Jatte. George has his great-grandmother's old grammar book and is idly intoning LESSON #8: "Charles has a book. . ." "Marie has the ball of Charles . . . " George misses Marie. And, as he thinks of her, Dot appears.

His great-grandmother has a special message for him. Despite his protestations that he has nothing more to say in his art, she urges him to move on and, as he reads the words Dot's Georges scribbled in her book a century ago, the original promenaders re-convene for one more perfect SUNDAY. George looks again at the book: "A black page or canvas. His favourite. So many possibilities . . . " The stage fades to white, and Dot slowly disappears.

Musical Numbers

Act One

- "Sunday in the Park with George" - Dot

- "No Life" - Jules, Yvonne

- "Color and Light" - Dot, George

- "Gossip" - Celeste #1, Celeste #2, Boatman, Nurse, Old Lady, Jules, Yvonne

- "The Day Off" - George, Nurse, Franz, Frieda, Boatman, Soldier, Celeste #1, Celeste #2, Yvonne, Louise, Jules, Louis

- "Everybody Loves Louis" - Dot

- "Finishing the Hat" - George

- "We Do Not Belong Together" - Dot, George

- "Beautiful" - Old Lady, George

- "Sunday" - Company

Act Two

- "It's Hot Up Here" - Company

- Chromolume #7 - George, Marie

- "Putting It Together" - George, Company

- "Children and Art" - Marie

- "Lesson #8" - George

- "Move On" - George, Dot

- "Sunday" (reprise) - Company

Philip's career crescendo

Aussie star snares top London role By Frank Gauntlett and Martin Kelly Daily Mirror 3 November 1989

THE Tamworth turkey farm where Philip Quast was raised may be light years away from the glamor of the London stage, but the rising star is not about to forsake his Aussie roots. He has followed up his local success as obsessive police chief Javert in the musical Les Misérables with a triumphant reproduction of the role at London's Palace Theatre. And now he has landed probably the most coveted role in UK theatre at the moment the lead in the National Theatre's production of Stephen Sondheim's Sunday In The Park With George.

Philip is also in the midst of recording the $800,000 double album of Jon English's spectacular musical epic of ancient Greece, Paris. Despite his stunning success, and the promise of more to come, Philip is longing for a bit of Australian sunshine and the chance to go fishing. But, with his present commitments, the simple pleasure of baiting a line may be months away.

"About a month ago when I auditioned for the National, I was really starting to look forward to coming home, doing a bit of fishing," Philip said from Surrey in England. Exactly when that will happen is difflcult to say at the moment. I finish Les Mis on December 2, then there is a 16-week season at the National before Sunday In The Park With George goes into repertoire. Then there's a chance that we will go on to Canada. but that hasn't been worked out yet."

Philip first made his reputation as a presenter of the ABC's Play School. But his stage career hit top gear with the Les Mis performance, which garnered him an army of fans, plus Sydney Theatre Critic Circle and Mo awards. The Sondheim role should be his biggest challenge. Philip has not yet seen a Sondheim musical. Right now he is more concerned with the recording of Paris with producer David Mackay.

Philip knows that all eyes (and some of them will be green with envy) will be watching for the slightest slip when he takes centre stage at the National next year. Still, if his past successes are any indication, Philip Quast will do us proud once again.

The Point about Sondheim

Review by Charles Osborne Daily Telegraphy 16/03/90 on the British premiere of 'Sunday in the Park with George'

THERE IS a distinct division of opinion in America about Stephen Sondheim. There are those who consider him the Broadway musical's only hope, and those who not only fail to see what all the fuss is about but are positively dismayed by his apparent disinclination to fill his shows with hummable tunes.

What is especially disconcerting to some and fascinating to others is Sondheim's refusal to go on writing the same kind of show. The composer of Follies, Pacific Overtures, Sweeney Todd, A Little Night Music and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum certainly deserves full marks for versatility.

Sunday in the Park with George, now at the National's Lyttelton Theatre, has taken its time to get to London. Opening in New York in 1985, it played for over 500 performances, mainly because people were bullied into seeing it by the critic of the New York Times, who wrote favourably about it so frequently that the show became known locally as “Sunday in the Times with George”.

But many in its audience were puzzled by what Sondheim was attempting to do, which was nothing less than to put on to the stage Georges Seurat's neo-lmpressionist painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, to describe its creation, and to say something about the nature of art.

When I first saw the show in New York, I thought it contained moments of sheer beauty embedded in an otherwise arid score and weighed down by a libretto, by James Lapine, of awesome pretentiousness and intellectual laziness. But I had learned, by then, always to give Sondheim the benefit of the doubt, for I had usually been won over on my second encounters with his musicals. And so it proved with this one, at least in part.

Act 1 introduces the painter, his model and mistress, and the various characters who inhabit his painting. Seurat's pointillist technique is cleverly paralleled by Sondheiin's wispy arpeggios and detached melodic phrases, varied by snippets of song which bring the personages of the painting alive without allowing them to overshadow the composer's main purpose: to show a work of art being brought to birth, harmony emerging from discord, Sunday, the choral number with which Act I ends, dazzlingly reproduces not only the shimmering haze of a summer afternoon but also something of the wonder of creation.

I still have difficulty with much of the anti-climactic Act 2 which relates awkwardly to general, but Sondheim's Act 1. The action has moved forward to the present day, and Seurat's great-grandson, George, a fashionably pretentious American pseudo-artist , who uses a machine to create his effects, is giving a ghastly audio-visual presentation of his latest work, Chromolume Number 7, in an American gallery.

This unamiable phoney is finally seen in Paris where he encounters the ghost of his great-grandfather's model in the now very urban-looking park. The ending, which attempts to repeat Act 1's remarkable vision of harmony, seems to sue facile. Nevertheless, throughout the act, Sondheim's score remains subtly fascinating. His tunes may, as someone once observed, sound like second viola parts but what original and imaginative second viola parts they are.

It may be 'caviar to the general', but Sondheim's score confirms me in my belief that he is one of the finest theatre composers of his generation. He is said to be not interested in opera, which is odd since what he writes has much more in common with the stage works of Michael Tippett and Aaron Copland than with those of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Jule Styne.

Steven Pimlott's smooth production is no mere replica of James Lapine's Broadway original, and Philip Quast (as Seurat and his great-grandson) is easily the equal of the New York lead (Mandy Patinkin). The role of Seurat's mistress in Act 1 is capably handled by Maria Friedman, who also plays his daughter in old age in Act 2. Sheila Ballantine is touching in the duet, Beautiful, sung by Seurat and his mother. Indeed, there are no weaknesses in a large cast. Sunday in the Park with George is well-worth seeing twice.

Review of Sunday in the Park with George

The creation conundrum by Michael Billington

The Guardian, 17th March 1990

Michael Billington, on a musical that brilliantly illuminates the joy and cost of producing great art.

STEVEN Pimlott's production of Sunday In The Park With George at the Lyttelton is startlingly different from the version I saw at New York's Booth Theatre five years ago: visually bolder, physically bigger, emotionally a little less charged. But Stephen Sondheim's music and lyrics and James Lapine's book retain their extraordinary wit and audacity: this is a genuine musical of ideas rather than simply a sumptuous divertissement.

It is built around the work of Seurat, a painter who applied rigorous analytical reason to art, and in particular his composition of Sunday On The Island Of La Grande Jatte. The first half shows the obsessive, pioneering Seurat working on the separate figures in his canvas, sacrificing his mistress, Dot, to his work and finally bringing the re-order reality and finally arrange the Sunday idlers into an harmonious composition: a gesture cynically echoed in the second act when George is busy fixing introductions and supplying drinks. But this is also a deeply personal show about the joys and the cost of creation; and what is startling about Sondheim's score is the way it corresponds to Seurat's own visual style. His pointilliste method is perfectly matched by the stabbing, jabbing, staccato music of Colour and Light. But Sondheim also uses what he calls "a rolling vamp" for Sunday, which movingly echoes the finished picture's majesty of colour and design.

This is the one point at which Mr Pimlott's production induces tears. But what is impressive is the way he and his partners, designer Tom Cairns and lighting-man Wolfgang Gobbel, have come up with a clean, clear visual concept different in many points from the New York original. The show begins and ends in a picture-framed, arctic-white box. By a dazzling trick of perspective, the second act starts with the figures of La Grande Jatte huddled together in an elevated, framed canvas. And where on Broadway the museum-scene was dominated by a laser-beam light-show it here becomes a satire on Robert Wilson-style performance-art: highly relevant since that too is about order, control and arranging bodies in space.

It is not a flawless show (thematic density cannot always make up for lack of narrative tension) but the two acts seem much more tightly integrated than they did in New York. The two lead roles are also superbly played. Philip Quast as the two Georges sharply contrasts the older one's monastic fervour with the younger one's gregarious emptiness and projects the words with clarity, elegance and style. Maria Friedman, as both Dot and her 98-year-old daughter Marie, also confirms she is an authentic star: she brings an earthy comedy to the chafing restrictions of Dot's existence, sings with note-true poignancy and has the gift of what Stanislavski called ''public solitude.'' In a large cast, Gary Raymond also shines out as both a velvet-smooth rival to Seurat and as a typical money-seeking modern museum-director. Jeremy Sams in the pit also ensures a balance between orchestral and vocal sound. Sunday in the Park makes you work. But it demands and re-pays the closest attention since it is a genuine pathfinder that proves the musical can not only deal with ideas, but illuminate the mystery of Creation itself.

'Sunday in the Park with George'

National Theatre, the Lyttelton Review by Steve Grant Time Out 21/03/90

Musicals are made out of strange subject matter but none come stranger than Stephen Sondheim's 1984 blending of pointillism, performance art and good old-fashioned 'Moulin Rouge' romance which typically, has taken six years and a good few helping hands to bring to London.

Thank God it's here at last and at a theatre with resources, time and craft to make it work well, because no matter what you think of Sondheim's attitude to harmony and melody (such as 'Does he have one?') you will not encounter an evening to rival this item in terms of sheer intellectual, visual and aural variety.

From the living colours of George Seurat's painting of a spring Sunday on the Isle of Grand Jatte to the Spy magazine enclaves of hip New York art houses to a final and touching image of regeneration and reunion, Sunday oozes life, light, wit and energy, particularly in this painstaking production masterminded by Steven Pimlott and designer Tom Cairns and despite its undoubted flaws in style and content.

It's certainly the case that the rather phlegmatic and episodic second half fails to match up to the promise of the first, nor is one wholly clear what Sondheim's attitude is to the piece of electronic performance art by which George, illegitimate descendant of Seurat, attempts communication with his dead forebear. Is George the avant-gardeist a valiant successor to his experimental great-grandfather, or a chiseler whose main facilities are a good electricity supply and a line in chat when canapés and champers come around?

Whatever the answer, Sondheim's own preoccupations remain very much with Seurat, a man who attempted to paint light by illusions made of colour, just as Sondheim's use of disparate musical effects attempts and finally achieves a moving harmony for his narrative and its narrators.

Superb and graceful sets, two wonderful leading performances from Philip Quast (Tom Conti meets Al Pacino) and Maria Friedman and a few two-dimensional dogs (the best kind) do nothing to interfere with one's glowing happiness on reentering the real and gloomy world of the South Bank and beyond. Go and see.

Strokes of Genius from an Old Master

Review by Jack Tinker Daily Mail 16/03/90

Sunday in the Park with George, music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim book by James Lapine: The Lyttelton

This is the kind of evening that turns a dear friend into a despised foe by the time the curtain falls.

Approach it with care and caution. But do not, whatever you do, miss it. For Sondheim's heroic leap into the bright unknown is as important as it is divisive.

Like the revolutionary painting that inspired it Georges Seurat's vast pointillist canvas Un Dimanche d'Ete a L'Ile de la Grande Jatte it glows with innovative technique and thrilling vision.

No-one before Seurat had thought of combining countless tiny dots of colour into one ordered image. By allowing the colours to mix in the eye of the beholder rather than on the palette of the painter, he brought a new dimension to art.

Sondheim and his libbretttist James Lapine work a similar revolution in terms of theatre. The lives frozen into the idyllic tableau by one medium are freed and explored by another.

Visually the piece is stunning. Whole sections of Seurat's painting come to life before one's eyes, spilling out the little vignettes which brought them to that park on those various Sundays, and then are carefully placed into the finished work by the artist himself.

Being a Sondheim subject, of course, it is no surprise that the artist had little life outside his art. He died at 31 having sold nothing and lost the only woman he loved, his appropriately named mistress, Dot.

The theme is worthy of Ibsen and might have matched the master builder had it not the rather superfluous second act attempted to bring us up to date and marry the past with the present in an awkward postscript.

Nonetheless, the concept is more than worthy of its Pulitzer Prize. The music, like the painting, comes in sharp, precise points with sound replacing colour.

And if nothing of this fires your imagination or thrills you admiration as it does mine, then go to see the iredescent Maria Friedman give glorious life to Dot, the downtroden, semi-literate mistress Seurat immortalised with giant perspective in the forefront of his painting. Philip Quast, Nyree Dawn Porter and Shelia Ballintine also bring their own distinction to Steven Pimlott's masterly production.

A collector's item worthy of the National.

Rehearsal photos from Sunday in the Park with George.

We would like to thank Matt for providing us with some of the reviews.

[UPDATES]

[BIOGRAPHY]

[ARTICLES

& INTERVIEWS ] [ STAGE

]

[ FILM & TV ][AUDIO/VIDEO ] [ LINKS] [SCRAPBOOK] [HOME ]

© Kate McCullugh & Angela Pollard 2001. No portion of this page may be

copied without permission of the author.